“Do you want to do something fun?” she said.

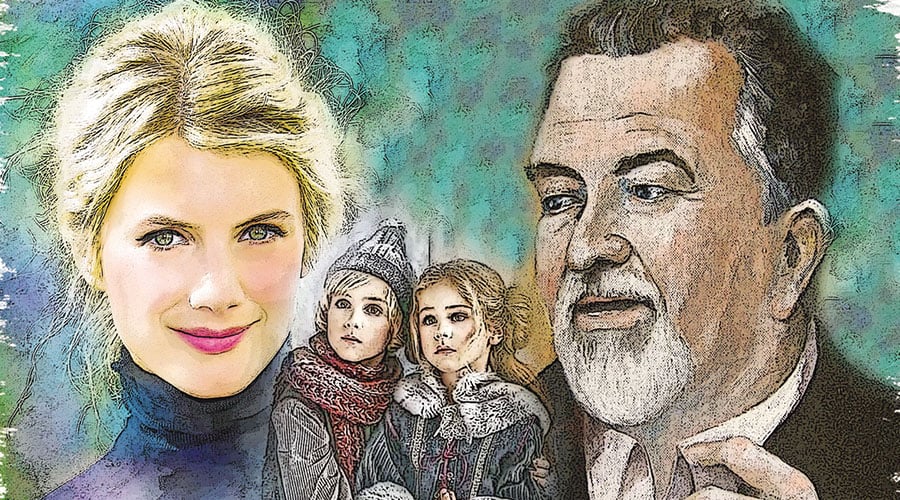

It was never my suggestion, but June Lilly was tall with long, shiny hair that sat on her shoulders the colour of swaying wheat. We looked up to her sapphire–eyed smile, haloed by the late evening sun, and when she snapped her fingers, we followed along like runty puppies yelping for attention. Everything about her was rich, evoked the perfume and grace of a palace garden.

June, her family, lived in a mansion. In the spinney next to the Common, discreetly surrounded by oaks and sycamores, the flowers burst into blossoms each spring and the house’s inhabitants were coddled in the sweet perfume of wealth.

We grew up the bland faced daughters of mailmen and waitresses, grease–blackened railway men and hard–edged prison warders, living in the outermost ripples of beauty and privilege. We were the Pamelas, Lindas and Janes that lived and died in the working class imagination and its drudging boredom.

We were looking for a way to lengthen, to improve the languid afternoon when June asked, dangling delicious possibilities in front of us like ripe pomegranates hanging low over a neighbour’s fence.

“Yes. I’m in.” I said, breathing just enough air into the words to let the idea float off innocuously but still be heard.

Linda’s eyes narrowed beneath her creasing brows.

“What’s the plan?” she asked, unwilling to throw herself carelessly into adventure, without asking the questions that swirled around on her face. Her father, a dour and dangerous man, told stories of runaway train engines, amputations and bodies cut in two because attention was lost and diligence abandoned. Caution thrown to the wind was always a dangerous thing.

The evening shuffled into night time, chasing all light and warmth into the mix of high–rise flats and fancy houses. A thick, tiptoeing cold took open streets and empty playgrounds hostage. Our mothers always told us to be home before the street lights came on, and we were already past daylight and creeping slowly into trouble.

“I need a jacket,” Pamela’s high pitched whine pierced through the gusts that suddenly whipped up the giant oaks and sent swirls of dead leaves to the sky. The prison guard’s daughter folded her goose fleshed arms across her chest with a loud shiver.

“I’m in,” she said, “as long as I can get a jacket.” The last word again cracked open by drama and the shiver. That was how Pamela was. Annoying and loud but intent on any mischief that she wouldn’t be caught in. A jailer for a dad was a terrible irony.

June’s eyes caught the sudden glare of the newly lit street lights. She pursed her lips, the corners of her mouth upturned, smug and victorious as she spoke.

“Well, I told the Taylor boys to meet us at 7:30 at The Wall.”

“No way!” Linda squealed. “I can’t. Do you know what…?” She stopped, and her whispered question lived and died in our heads, unanswered. Of course, we knew ‘what.’ We saw the welts and bruises painted over with her mother’s gaudy makeup, too orange, too fake, for a pale and freckled twelve–year–old.

“I’m free–zing.” Pamela complained again. “We’ll drop by my house on the way. Get a coat.”

June’s casual suggestion had rolled so quickly into a foregone conclusion.

“What about our parents?” I asked. Pamela looked around our circle of sudden conspirators, a tiny smile almost escaping unnoticed.

“Gone to Bingo,” she said.

“C’mon, little Lindy. How about it?” June grabbed the undecided girl’s arm, pulled her tightly to her side in an unusual display of affection. “We won’t be too late home.”

Buoyed by the sudden and surprising closeness, Linda surrendered.

I studied June’s eyes, glittering under the lamplight, and dared to challenge,

“What about your parents? Won’t you be in deep shit?”

“Not a problem,” she said. “They believe anything I tell them.”

And with that, the deal was done.

Pamela emerged from her flat, high up in the austere monolithic block that overlooked the west side of Hexton Prison. We could hear her footsteps scattering quickly along the concrete walkways that ran in grey parallel lines across the front of the building. Pamela scurried along each one left to right, clattering down the iron steps, turning, and running along the next lower walkway, right–left.

Past the rows of utility–green painted front doors until eventually she emerged. A bright pink jacket was tied around her thin waist, a shiny–red heart–shaped bag slung carelessly over her shoulder. Pamela’s chest heaved in and out as she caught spent breath, her voice cut by the effort.

She called, breathless, emerging where the ground–floor walkway ended and into a concrete arch lined with cracked green tiles. The wind exhaled across the asphalt apron where we waited, carrying the pungent smell of stale urine and overflowing garbage. None of us cared. The boys were close.

Their breaking voices blew loudly in our direction, the only discernible sound in the night. Like playful colts, three of the youths pushed and jostled against each other but a fourth, taller and brawnier, walked beside them, seemingly disinterested in their juvenile shenanigans. One tiny orange glow and the familiar unfiltered smell of excitement drifted closer. In seconds the group had reached us on the dark asphalt apron that spanned between the building and the immense and overshadowing wall.

June spoke first, clearly irritated. “I didn’t know you were coming.” She grabbed the cigarette from the bigger boy’s fingers and lifted it to her lips, drawing in a lingering mouthful of cheap smoke.

“Shut up, sis.” He said. “I thought it might be an interesting night.”

June exhaled, releasing slow grey curls across the dimly lit air. “What about the oldies?”

“Out.” A devious smile crossed her brother’s face.

“Alright, Terry, you can stay but no trouble.”

I knew Terry Lilly only from rumours, and here he stood in front of us, big as a bear, casting a solid black shadow on the asphalt as daylight finally gave up. His face was as ungainly as his huge body. Startlingly thick lips pursed around the cigarette, strong black hairs sprouted from his chin and cheeks. A few dark curls fell over his large forehead, and cascaded down the collar of his jacket, turned up to keep the biting wind at bay. He was seventeen and already had the looks of a man. A man to be wary of.

“You girls want to go for a walk?” He asked his voice as deep as my father’s.

“Yeah. Let’s go for a walk.” Grant Taylor, the youngest of the three brothers, jumped on board, his voice bubbling like a shaken soda.

The middle brother, Jimmy, was very different. Neither funny nor sporting, he was an enigma to his parents and his peers, choosing to stay home and read on a sunny afternoon, to roam the streets in a storm. To me, he was the interesting Taylor brother, the one that deeply challenged the curiosity of a thirteen–year–old girl.

We walked towards The Wall in two groups, us girls chattering among ourselves, making nervous small talk about the weather and the weekend, anything except about what we hoped was about to happen. Terry offered the boys a smoke and each, except Jimmy, flipped back the gold embossed lid, deftly picked one out and planted it between his lips. Grant and Greg waited for the flame of Terry’s silver lighter.

“Want one?”

I spun around, Terry’s voice breaking through the excited chit–chat and nervous giggles.

“No, no thanks. I don’t.” I said, but he persisted, holding me in a look that jangled my nerves the way sudden weather catches wind chimes in a discordant clang.

“Yes… okay. Thanks.” I took my first cigarette, lifted it to my mouth as one of Terry’s enormous hands cupped around it and the other struck the lighter.

And then he spoke, burning my ears with his quiet insistence.

“Come to The Wall with me, kid.”

Repulsed by breath that smelled like raw meat and stale smoke, I fumbled and coughed, the cigarette searing the back of my throat. His dark eyes pinned me down to answer. A light glisten of moisture broke onto my palms. I was sure a deep red flush had risen on my cheeks but could he possibly be joking? Making some fearful joke that I was supposed to understand, rebuff, and brush away with a coy giggle? But I saw his eyes roll in impatience, heard an annoyed sigh and felt the growing tension in his pressing body.

“No, no.” I said. My invincibility, my confidence, spiralled up and away into the blue–black sky with the reeking smoke that burned between my fingers.

“No, Terry,” a firm male voice broke the silence. “I’ve already asked her. She’s coming to The Wall with me.” Jimmy pulled at my hand and I let the half lit cigarette fall, ashes trailing after it to a dimming glow on the ground.

Terry gave another guttural sigh, shrugged and walked back to the group. I saw him whisper into June’s silky hair, and she turned to look at me, eyebrows raised in a question I did not understand.

I was still holding Jimmy’s hand, as we walked almost the length of The Wall, and then stopped. The girls, Terry, the other two Taylor boys, had all been swallowed by distance, melted into the dark.

“You’re pretty.” Jimmy’s voice was low and quiet, having difficulty forming, and I had the idea that he was more used to silence than the rest of us.

I nodded to The Wall and asked,

“What do you think it’s like in there?”

We both craned to look up, trying to get a sense of the prison from the enormity of the walls that were sealing it in. The endless grey bricks stretched up to disappear into inky clouds, a medieval fortress built to keep the evil in, not out.

His reply broke the silence.

“Lonely,” he said.

I lowered my gaze to find his eyes, surprised by our proximity, and a sudden urge to find his mouth with mine, but Jimmy turned his head and stepped back.

“Be careful around that Terry guy,” he said. “And that sister of his is a bitch.” Confusion bubbled in my stomach, rose to my mouth as unformed anger.

“Don’t talk about her like that. June is my best friend,” I remembered Pamela and Linda, back at the flats with the other Taylor boys, and Terry, and corrected; “She’s our best friend.”

Jimmy smiled and shrugged.

“Well, I warned you,” he said, his voice flat. He extracted an unfinished cigarette from his pocket and lit it. Leaned back against The Wall.

I turned and ran, following the thick shadow of The Wall for what seemed like miles, until I reached our spot, outside the flats. Our agreed meeting place. Stale urine and overflowing garbage remained, but my friends were already gone.

Mum had left for work even earlier that morning and dad sat tight–mouthed at the breakfast table, hiding behind a newspaper until I spoke.

The teacher entered, late and oblivious, and hurried to the large desk at the front of the room. Voices, the noise of shifting bodies, returned. As if nothing had interrupted its busy flow. I hurried to throw the displayed contents of my life into the bag. Then sat.

For the next two days my bag was tipped out whenever I left it unattended until I learned not to. The word SLUT was added to the surface of my desk, etched crude and generic, not just to warn me, but future generations, of the dangers of being adolescent.

On the third day it all stopped. As I walked into school, Pamela and Linda were standing under the huge sycamore that shaded the pathway to the main entrance outside the school.

“Do you guys know who started all this shit?” I asked. “Was it Grant?” Their faces blanked, unblinking.

“Greg?” No response.

There was no logic to saying Terry’s name. He was a much bigger fish in this goldfish bowl–sized world of Grammar School and teenage bullying.

I inhaled as the question formed. It was the last deep breath of naivete, of teenage innocence. And trust.

“It was June.” What began as a question morphed into a bold statement of awareness, and I exhaled.

Pamela and Linda, who wore the swollen, purple badge of violence across her right eye, passed the truth between themselves. A secret, a confession, and an apology.

I thought about Jimmy and his warning, and wondered how he knew. What she had done to him to make him know. That didn’t seem to matter now. But if I ever saw him again, I would ask.

I thought about all this; family, wealth and walls, as I trudged across the Common toward home, and suddenly loved my friends, my parents, more than I had ever loved them before.

– Anonymous